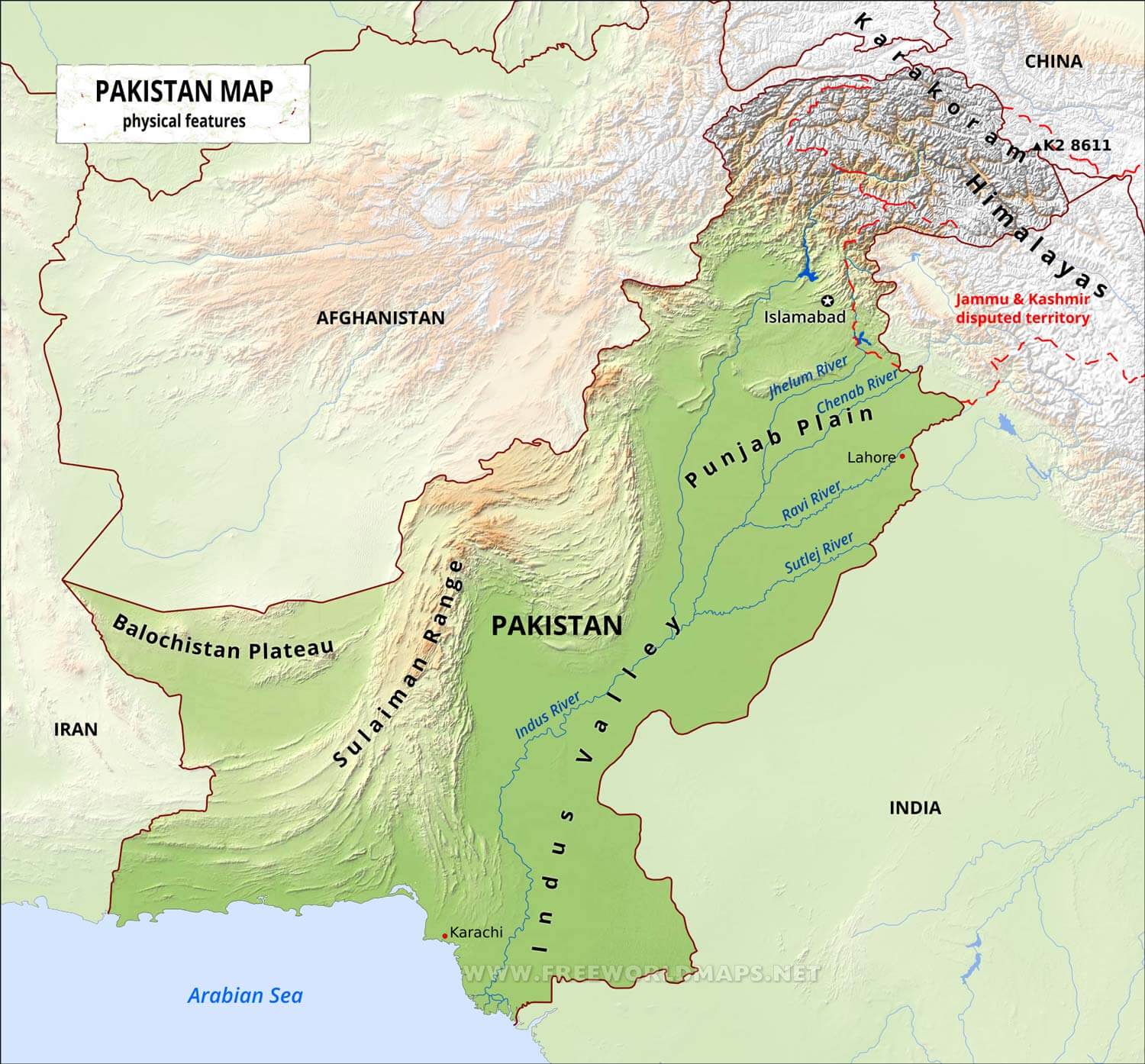

The Geography of Pakistan is a profound blend of landscapes varying from plains to deserts,

forests, and plateaus ranging from the coastal areas of the Arabian Sea in the south to the mountains of the

Karakoram,

Hindukush, Himalayas ranges in the north. Pakistan geologically overlaps both with the Indian and the

Eurasian tectonic

plates where its Sindh and Punjab provinces lie on the north-western corner of the Indian plate while

Balochistan and

most of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa lie within the Eurasian plate which mainly comprises the Iranian Plateau.

Pakistan is bordered by India to the east, Afghanistan to the northwest and Iran to the west while China

borders

the country in the northeast. The nation is geopolitically situated within some of the most controversial

regional boundaries

which share disputes and have many-a-times escalated military tensions between the nations, e.g., that of

Kashmir with India and

the Durand Line with Afghanistan. Its western borders include the Khyber Pass and Bolan Pass that have

served as traditional migration routes between Central Eurasia and South Asia.

At 881,913 square kilometres (340,509 sq mi), Pakistan is the 33rd largest country by area,

little more than twice the size of the US state of California, and slightly larger than the Canadian

province of Alberta.

Pakistan shares its borders with four neighboring countries - People's Republic of China, Afghanistan, India, and Iran while Tajikistan is separated by thin Wakhan Corridor– adding up to about 7,307 km (4,540.4 mi) in length (excluding the coastal areas).

Pakistan is divided into three major geographic areas: the northern highlands; the Indus River plain, with

two major subdivisions corresponding roughly to the provinces of Punjab and Sindh;

and the Balochistan Plateau.Some geographers designate additional major regions.

For example, the mountain ranges along the western border with Afghanistan are sometimes described

separately from the Balochistan Plateau,

and on the eastern border with India, south of the Sutlej River, the Thar Desert may be considered

separately from the Indus Plain.

Nevertheless, the country may conveniently be visualized in general terms as divided in three by an

imaginary line drawn eastward from the Khyber Pass

and another drawn southwest from Islamabad down the middle of the country. Roughly, then, the northern

highlands are north of the imaginary east-west line;

the Balochistan Plateau is to the west of the imaginary southwest line; and the Indus Plain lies to the

east of that line.[citation needed]

The northern highlands include parts of the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram Range, and the Himalayas.

This area includes such famous peaks as K2[3] (Mount Godwin Austen, at 8,611 meters the second highest peak

in the world).

More than one-half of the summits are over 4,500 meters, and more than fifty peaks reach above 6,500 meters.

Travel through the area is difficult and dangerous, although the government is attempting to develop certain

areas into tourist and

trekking sites. Because of their rugged topography and the rigors of the climate,the northern highlands and

the Himalayas to the east have been formidable barriers to movement into Pakistan throughout history.

South of the northern highlands and west of the Indus River plain are the Safed Koh Range along the

Afghanistan border and the Suleiman Rangeand Kirthar Range,

which define the western extent of the province of Sindh and reach almost to the southern coast.

The lower reaches are far more arid than those in the north, and they branch into ranges that run generally

to the southwest across the province Balochistan.

North-south valleys in Balochistan and Sindh have restricted the migration of peoples along the Makran Coast

on the Arabian Sea east toward the plains.

Several large passes cut the ranges along the border with Afghanistan.

Among them are the Khojak Pass, about eighty kilometres northwest of Quetta in Balochistan; the Khyber Pass,

forty kilometres west of Peshawar and leading to Kabul; and the Broghol Pass in the far north, providing

access to the Wakhan Corridor.

Less than one-fifth of Pakistan's land area has the potential for intensive agricultural use.

Nearly all of the arable land is actively cultivated, but outputs are low by world standards.

Cultivation is sparse in the northern mountains, the southern deserts, and the western plateaus, but the

Indus River basin in Punjab and northern Sindh has fertile soil

that enables Pakistan to feed its population under usual climatic conditions.

The name Indus comes from the Sanskrit word hindu, meaning ocean, from which also come the words Sindh,

Hindu, and India.

The Indus, one of the great rivers of the world, rises in southwestern Tibet only about 160 kilometres west

of the source of the Sutlej River,

which first flows through Punjab, India and joins the Indus in Pakistani Punjab, and the Brahmaputra, which

runs eastward before turning southwest

and flowing through India and, Bangladesh. The catchment area of the Indus is estimated at almost 1 million

square kilometres,

and all of Pakistan's major rivers—the Kabul, Jhelum, and Chenab—flow into it. The Indus River basin is a

large, fertile alluvial plain formed by silt from the Indus.

This area has been inhabited by agricultural civilizations for at least 5,000 years.

Balochistan is located at the eastern edge of the Iranian plateau and in the border region between

Southwest, Central, and South Asia.

It is geographically the largest of the four provinces at 347,190 km² (134,051 square miles) of Pakistani

territory; and composes 48% of the total land area of Pakistan.

The population density is very low due to the mountainous terrain and scarcity of water.

The southern region is known as Makran. The central region is known as Kalat.

The Sulaiman Mountains dominate the northeast corner and the Bolan Pass is a natural route into Afghanistan

towards Kandahar.

Much of the province south of the Quetta region is sparse desert terrain with pockets of inhabitable towns

mostly near rivers and streams.

The largest desert is the Kharan Desert which occupies the most of Kharan District.

This area is subject to frequent seismic disturbances because the tectonic plate under the Indian plate

hits the plate under Eurasia as it continues to move

northward and to push the Himalayas ever higher.

The region surrounding Quetta is highly prone to earthquakes. A severe quake in 1931 was followed by one of

more destructive force in 1935.

The small city of Quetta was almost completely destroyed, and the adjacent military cantonment was heavily

damaged.

At least 20,000 people were killed. Tremors continue in the vicinity of Quetta.

The most recent major earthquakes include the October 2005 Kashmir earthquake in which nearly 10,000 people

died[4] and the 2008 Balochistan earthquake occurred in

October 2008 in which 215 people were killed. In January 1991 a severe earthquake destroyed entire villages

in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa,

but far fewer people were killed in the quake than died in 1935.

A major earthquake centered in the Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa's Kohistan District in 1965 also caused heavy damage

Pakistan lies in the temperate zone, immediately above the tropic of cancer.

The climate varies from tropical to temperate. Arid conditions exist in the coastal south, characterized by

a monsoon season

with adequate rainfall and a dry season with lesser rainfall, while abundant rainfall is experienced by the

province of Punjab,

and wide variations between extremes of temperature at given locations.

Rainfall varies from as little as less than 10 inches a year to over 150 inches a year, in various parts of

the nation.

These generalizations should not, however, obscure the distinct differences existing among particular

locations.

For example, the coastal area along the Arabian Sea is usually warm, whereas the frozen snow-covered ridges

of the Karakoram Range

and of other mountains of the far north are so cold year round that they are only accessible by world-class

climbers for a few weeks in May and June of each year.